1. Introduction

Pumping stations are critical to municipal water supply, industrial process loops, and wastewater treatment, but they face a severe threat: water hammer. This hydraulic shock occurs when fluid velocity changes abruptly (e.g., sudden pump shutdowns), generating pressure surges that can burst pipelines, damage pumps, and cause costly outages. Traditional mitigation tools like surge tanks or relief valves have limitations—surge tanks require space and capital, while relief valves may lag in response.

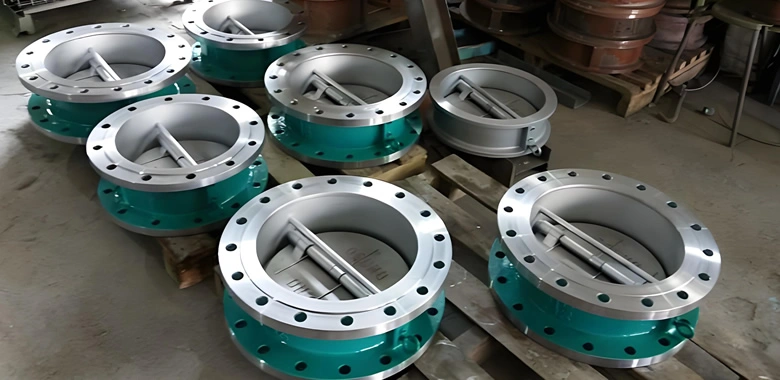

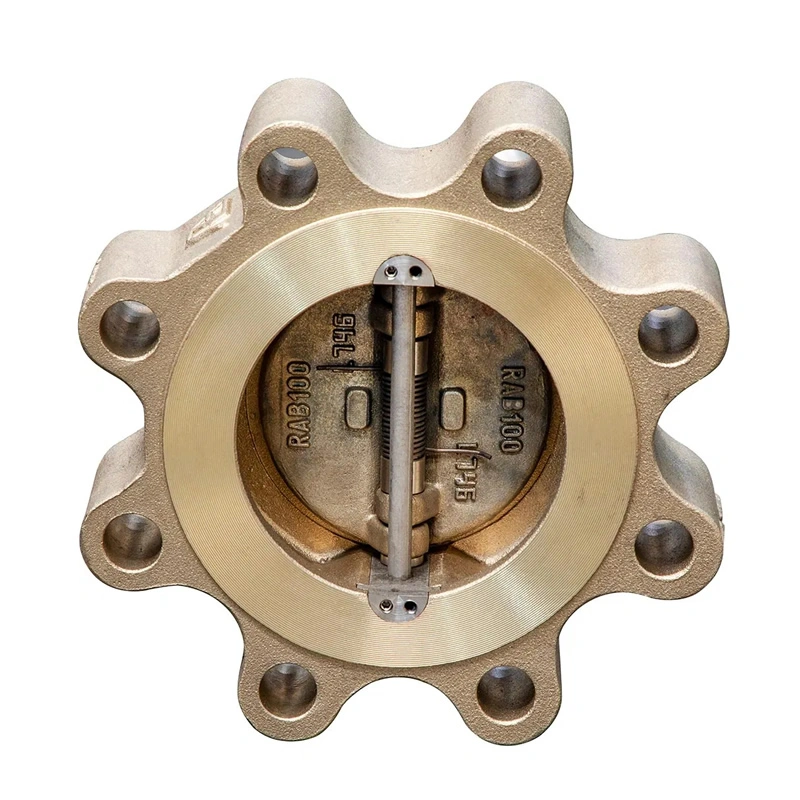

Dual plate check valves (double door check valves) emerge as a compact, cost-effective solution. Their unique design enables rapid, controlled closure to arrest reverse flow and dampen surges, while maintaining low flow resistance during normal operation. This article explores their role in water hammer prevention, covering core principles, design, performance, selection,installation, and real-world applications.

2. Fundamentals of Water Hammer in Pumping Stations

2.1 The Physics of Water Hammer

Water hammer stems from fluid inertia. When flow stops suddenly, kinetic energy converts to pressure energy, creating a shock wave traveling at 1,000–1,400 m/s (sound speed in water). The Joukowsky Equation quantifies initial pressure surges:

\(\Delta P = \rho c \Delta v\)

- \(\Delta P\) = Pressure surge (kPa/psi)

- \(\rho\) = Fluid density (1,000 kg/m³ for water)

- \(c\) = Wave speed (m/s)

- \(\Delta v\) = Change in velocity (m/s, equal to operating velocity if flow stops fully)

For example, a cast iron pipeline (\(c=1,200\) m/s) with \(v=2.5\) m/s generates \(\Delta P=3,000\) kPa (435 psi)—doubling the design pressure of many systems. Reflected waves from pipe boundaries further amplify oscillatory pressure cycles, worsening component wear.

2.2 Primary Causes and Risks

Table 1 summarizes common triggers and their impacts:

|

Cause of Water Hammer

|

Mechanism

|

Risk Level (1–5)

|

Typical Consequence

|

|

Sudden Pump Shutdown

|

Power failure halts flow; reverse flow may occur

|

5

|

3,200 kPa surge in DN1000 pipelines

|

|

Rapid Valve Closure

|

Valves close faster than fluid decelerates

|

4

|

2,800 kPa spike in downstream lines

|

|

Reverse Flow

|

Check valve failure damages pump impellers

|

4

|

Mechanical seal failure; pressure oscillations

|

|

Flow Demand Drops

|

Sudden reduced demand converts kinetic to pressure energy

|

2

|

800 kPa surge in distribution lines

|

Unmitigated water hammer leads to pipeline bursts (\(50k–\)500k repairs), pump damage (\(15k–\)100k per unit), and service outages (12–96 hours), with municipal systems facing fines for non-compliance.

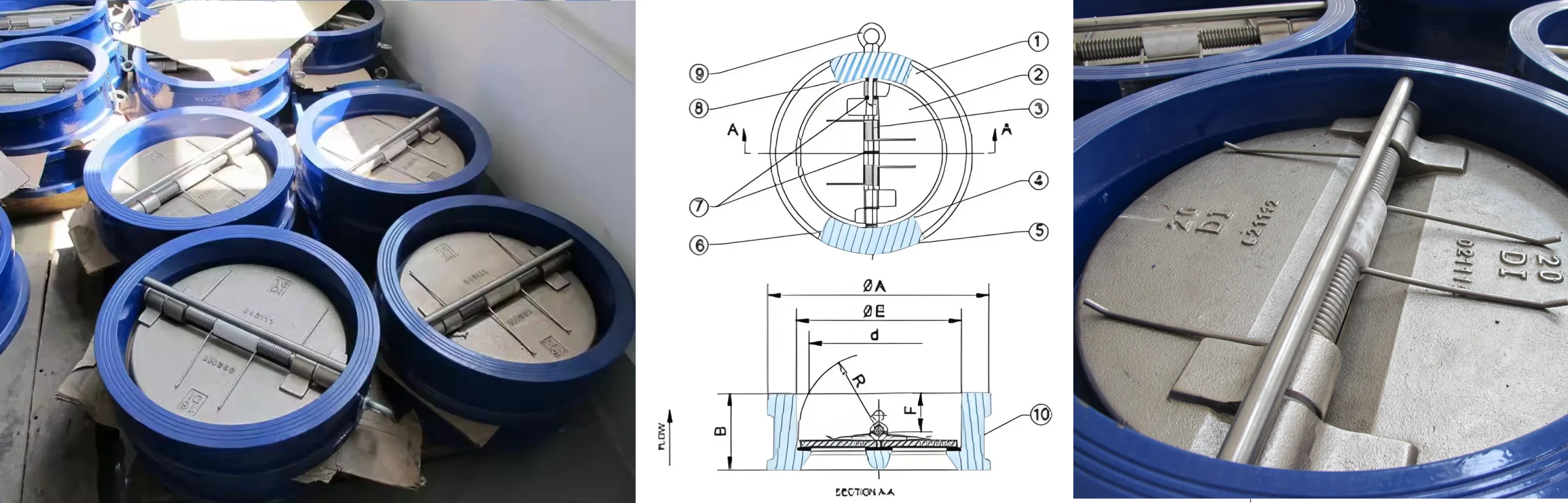

3. Design Principles of Dual Plate Check Valves

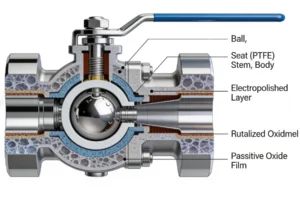

3.1 Core Components and Materials

Dual plate check valves rely on five key parts, with material selection tailored to media and operating conditions (Table 2):

|

Component

|

Material Option

|

Temp Range

|

Pressure Rating

(PN)

|

Corrosion

Resistance (1–5)

|

Typical Application

|

|

Valve Body

|

Ductile Iron (ASTM A536)

|

-20°C–120°C

|

PN1.0–PN4.0

|

3

|

Municipal water/wastewater

|

|

316 Stainless Steel

|

-196°C–538°C

|

PN1.0–PN6.3

|

5

|

Saltwater/industrial effluent

|

|

|

Dual Discs

|

Ceramic-Coated Steel

|

-50°C–300°C

|

PN2.5–PN6.3

|

5

|

High-solids wastewater

|

|

EPDM-Coated 304 SS

|

-40°C–150°C

|

PN1.0–PN4.0

|

4

|

Hot water/food processing

|

|

|

Hinge Pin

|

316 Stainless Steel

|

-196°C–538°C

|

PN1.0–PN6.3

|

5

|

Corrosive media

|

|

Return Spring

|

Inconel 718

|

-270°C–704°C

|

PN1.0–PN6.3

|

5

|

High-temp/corrosive environments

|

|

Seat Ring

|

PTFE

|

-200°C–260°C

|

PN1.0–PN4.0

|

5

|

Chemical-resistant applications

|

3.2 Working Mechanism

The valve operates in three phases:

- Forward Flow: Fluid force pushes discs open (60–80°) against the spring, minimizing pressure drop. A DN500 valve has a \(C_v\) of 2,500–3,000 (vs. 1,800–2,200 for swing check valves), cutting pump energy use by 3–5%.

- Pump Shutdown: As flow decelerates, spring torque initiates closure. Closure times (0.5–2.0 s) are calibrated to match fluid deceleration; optional cam mechanisms reduce seat wear.

- Reverse Flow Prevention: Discs seal against the seat ring, meeting API 598 leakage standards (<0.1 mL/min per inch of diameter for potable water).

API JIS DIN CLASS 300 Flanged Carbon Steel/Stainless Steel Swing Check ValveTable 3 compares surge mitigation vs. swing check valves (DN800, \(v=2.0\) m/s):

|

Valve Type

|

Closure Time (s)

|

Initial Surge (kPa)

|

Peak Oscillation (kPa)

|

|

Dual Plate (Stiff Spring)

|

1.2

|

1,800

|

2,100

|

|

Dual Plate (Soft Spring)

|

1.8

|

2,200

|

2,400

|

|

Swing Check

|

4.5

|

3,200

|

3,800

|

3.3 Key Design Innovations

- Adjustable Spring Stiffness: Interchangeable springs tune closure time (e.g., 0.8 s for high-velocity lines, 1.8 s for long pipelines).

- Wear-Resistant Coatings: Ceramic coatings extend disc life by 300–500% in wastewater; WEF studies show 8–12 years of service vs. 3–5 for uncoated valves.

- CFD-Optimized Flow Paths: Computational fluid dynamics reduce pressure drop by 15–25% and eliminate disc flutter.

4. Performance Metrics

4.1 Closure Time

The critical metric for surge control, closure time (\(T_c\)) should be 50–75% of the pipeline’s transient response time (\(T_R = 2L/c\), where \(L\) = pipeline length, \(c\) = wave speed). Table 4 lists recommended \(T_c\) values:

|

Pipeline Length (L)

|

Wave Speed (c)

|

\(T_R\) (s)

|

Recommended \(T_c\) (s)

|

|

500 m

|

1,200 m/s

|

0.83

|

0.42–0.62

|

|

1,000 m

|

1,200 m/s

|

1.67

|

0.83–1.25

|

|

2,000 m

|

1,200 m/s

|

3.33

|

1.67–2.50

|

4.2 Pressure Drop

Measured via flow coefficient (\(C_v\): gpm of water at 1 psi drop). Table 5 compares \(C_v\) values:

|

Valve Diameter (DN)

|

Dual Plate (Cv)

|

Swing Check (Cv)

|

Lift Check (Cv)

|

|

200

|

1,200–1,400

|

800–1,000

|

500–600

|

|

500

|

6,000–6,500

|

4,500–5,000

|

2,500–3,000

|

|

800

|

15,000–16,000

|

11,000–12,000

|

6,000–7,000

|

For a DN500 valve at 10,000 gpm, \(\Delta P = 8.33 \times (10,000/6,250)^2 = 21.3\) psi (147 kPa)—62% lower than swing Check Valves.

4.3 Leakage and Fatigue

- Leakage: API 598 requires no visible leakage at 1.1× rated pressure; potable water systems demand <0.1 mL/min per inch of diameter.

- Fatigue Resistance: Valves withstand 100k–1M cycles. Service life ranges from 3–5 years (high-solids wastewater) to 15–20 years (fire protection standby).

5. Sizing and Selection

5.1 Step-by-Step Selection

- Gather Hydraulic Data: Nominal diameter (DN), flow rate (\(Q\)), operating pressure (\(P\)), velocity (\(v\)), pipeline length (\(L\)), and fluid temperature (\(T\)).

- Evaluate Media: Corrosiveness (e.g., saltwater needs 316 SS), abrasiveness (high solids need ceramic discs), and sanitary requirements (NSF/ANSI 61 for potable water).

- Calculate \(C_v\): Ensure \(C_v \geq Q \times \sqrt{\rho/\Delta P}\) (max \(\Delta P\) = 5–10% of \(P\)).

- Determine \(T_c\): \(T_c = 0.5–0.75 \times T_R\).

- Verify Standards: PN ≥ 1.5×(\(P + \Delta P_{\text{surge}}\)); API 598 leakage, API 607 fire safety (industrial).

5.2 Common Pitfalls

- Oversizing: Larger valves cause flutter (velocity <0.5 m/s) and accelerate wear.

- Ignoring \(T_c\): A valve with \(T_c=3.0\) s in a pipeline with \(T_R=2.73\) s amplifies surges.

- Mismatched Materials: Ductile iron fails in saltwater; use 316 SS instead.

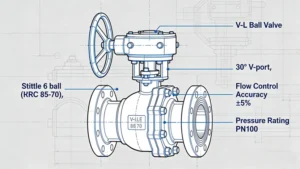

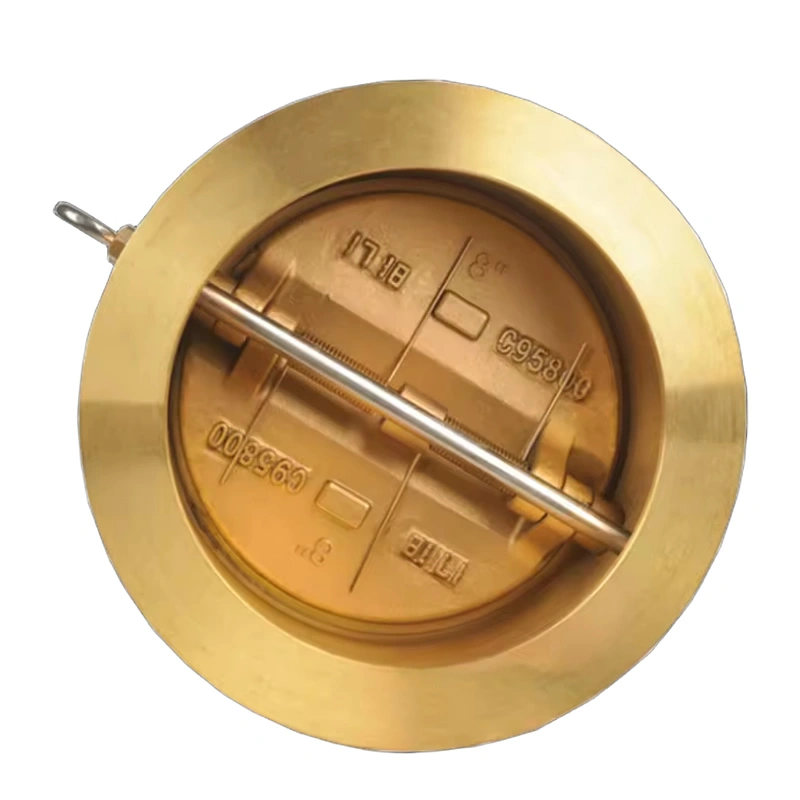

Dual Plate Brass Swing Check Valve 6 Inch Double Disc Bronze Wafer Check Valve

6. Installation Best Practices

- Orientation: Horizontal installation (vertical upward flow needs 20–30% stiffer springs; downward flow is not recommended). Flow arrow must point from pump to pipeline.

- Alignment: Valve centerline = pipeline centerline (max misalignment ±0.5 mm/m). 5× DN upstream straight run, 3× DN downstream to reduce turbulence.

- Gaskets: Match material to media (EPDM for potable water, PTFE for chemicals). Torque bolts in a star pattern.

- Testing: Hydrostatic test (1.5× \(P\) for 30 minutes); functional test at 50–100% flow; shutdown test to verify \(T_c\).

7. Maintenance and Troubleshooting

7.1 Preventive Maintenance Schedule

Table 6 outlines frequency by application:

|

Task

|

Municipal Water

|

Wastewater

|

Industrial

|

|

Visual Inspection

|

Monthly

|

Biweekly

|

Weekly

|

|

Leakage Check

|

Quarterly

|

Monthly

|

Biweekly

|

|

Spring Tension Check

|

Annually

|

Semi-Annually

|

Quarterly

|

|

Full Overhaul

|

8–12 Years

|

5–8 Years

|

3–5 Years

|

7.2 Common Issues

|

Symptom

|

Cause

|

Solution

|

|

Increased Leakage

|

Seat wear/debris

|

Replace seat; clean seat

|

|

Reduced \(T_c\)

|

Spring degradation

|

Replace spring

|

|

Disc Flutter

|

Velocity <0.5 m/s

|

Increase flow; downsize valve

|

8. Case Studies

8.1 Municipal Water (Los Angeles, USA)

- Problem: Swing check valves caused 3,800 kPa surges; 2 pipeline bursts ($320k repairs).

- Solution: DN1000 dual plate valves (\(T_c=1.2\) s, ceramic discs) + pressure relief valve.

- Results: 42% surge reduction (to 2,200 kPa); 4.2% energy savings ($18.5k/year); 3 years leak-free.

8.2 Wastewater (London, UK)

- Problem: Swing valves needed 6-month maintenance ($8k/cycle) due to abrasion.

- Solution: DN600 dual plate valves (ceramic discs, \(T_c=1.0\) s) + 1 mm strainer.

- Results: 80% wear reduction; 2-year maintenance intervals; 39% surge reduction.

9. Comparison to Other Mitigation Devices

Table 7 compares options for a DN800 station:

|

Device

|

Initial Cost ($)

|

Surge Reduction (%)

|

Space

|

Service Life (Years)

|

|

Dual Plate Valve

|

15k–20k

|

40–60

|

Compact

|

8–12

|

|

Surge Tank

|

150k–250k

|

70–90

|

Large

|

20–30

|

|

Pressure Relief Valve

|

8k–12k

|

20–30

|

Compact

|

5–8

|

|

Air Chamber

|

30k–50k

|

50–70

|

Medium

|

10–15

|

Dual plate valves offer the best balance of cost, space, and performance for most applications.

10. Future Trends

- Smart Valves: IoT sensors (pressure, vibration, position) enable real-time monitoring; machine learning predicts maintenance needs (45% less downtime in pilots).

- Advanced Materials: Graphene-coated discs (1,000% wear resistance); SMA springs (auto-adjust stiffness with temperature).

- Digital Twins: Virtual models optimize selection and simulate surges (60% fewer selection errors).

Dual plate check valves are a technically superior solution for pumping station water hammer prevention. Their compact design, cost-effectiveness, and ability to reduce surges by 40–60% make them indispensable. By following proper selection,installation, and maintenance practices—paired with emerging smart technologies—engineers can ensure long-term reliability, energy savings, and compliance with strict operational standards. As pumping systems evolve, these valves will remain a cornerstone of efficient, safe fluid control.